NASA”s Centennial Challenge is an annual competition targeted at university students for the purposes of science outreach. Teams of 10 students receive instructions for a project goal and must complete it on a strict timeline and strict rules. Throughout the process you have to report your progress through extensive documentation and meetings with NASA engineers.

As a high school team, we had been competing in NASA’s kid-friendly version of the competition for many years (though much of that was before my time). In my junior year of high school, outreach coordinators reached out to our rocketry team and asked if we would like to try out hand in the big boi leagues :0. Naturally we said yes.

What we were getting ourselves into

That year’s project was to build two things: a Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV) and an Autonomous Ground Support Equipment (AGSE). The premise is that sending complex robots to Mars to do analysis of the surface would be too costly money-wise and time-wise. Instead, if there were a simple system based on the surface of Mars that could collect interesting samples and launch them either back to Earth or a space station then that could save on a lot of cost and development time.

Obviously we weren’t going to be building anything that could actually work in this scenario. Instead our MAV needed to fly as close as possible to a one mile apogee (peak point) and the AGSE needed to retrieve a cylindrical payload from the ground in a fixed location, place it into the MAV, and prep the MAV for launch.

As a more senior member of the rocketry club by this time, I ended up signing up for the project because it sounded cool. Although, looking through the retrospective lens, I really enjoyed the experience of working on the project, the actual work and labor was really rough and not glamorous at all.

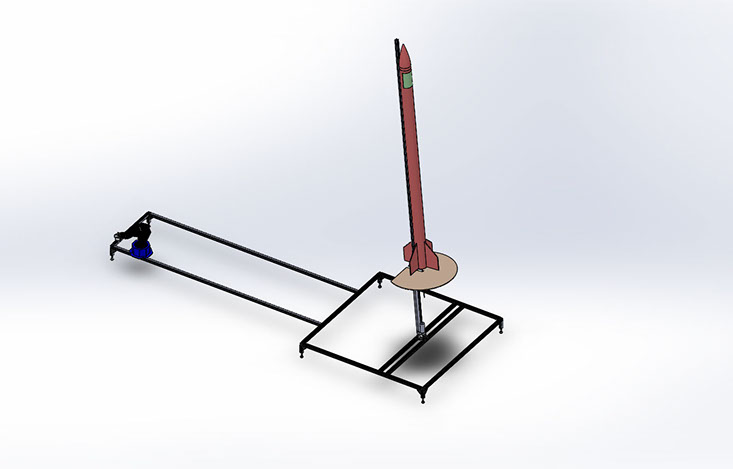

An initial 3D render of our system

An initial 3D render of our system

How were we gonna do this??

The MAV was easy. As a club, we had plenty of experience in building rockets and a one mile apogee was easy to spec and build. Something like that AGSE, though, was something that we had never tried to build before.

In true NASA and space travel fashion, the spec requirement for the AGSE included tight weight and dimension restrictions. Because of these restrictions, we could not afford to use powerful motors or heavy off-the-shelf robotic arms. This meant that we were going to have to build a lot of the AGSE from scratch, a really daunting prospect.

We did have on advantage over every other team: our club did a lot of raking. Yup that’s right. In order to fund the club, we would split up into groups and trek all over Madison, Wisconsin during autumn to find people willing to donate money in exchange for our (rocket powered) raking services. We always kept some rakes laying in our workshop to make sure we were never short on funding tools.

The breakthrough technology for the AGSE we had been looking for was actually rake clips, for hanging our precious funding tools on the walls. Since the target payload was guaranteed to be a cylindrical shape, we could use 1 rake clip on the robot arm as the gripper and 2 rake clips inside the rocket as the holder. This way the 1 to 2 rake clip force differential would allow the payload to be transferred passively. No gripper control, no code, just high level engineering.

An initial fabrication of our system

An initial fabrication of our system

Presenting to NASA engineers (and waking up super early)

To keep up with our progress, we had consistent check-ins with our assigned NASA engineers.

It is completely possible to fail the challenge at any of these check-in points so it was critical to write really good documentation and have a well-rehearsed presentation. The Critical Design Review and the Flight Readiness Review were the two important ones that were actually pretty nerve-wracking to present.

Since the NASA engineers needed to get these meetings out of the way before their work day really started, this meant waking up hella early to attend these check-ins.

The documentation and presentations from our check-ins are linked down below. If you are somehow way too bored, you can go take a look. Though I wouldn’t recommend reading through any of them as they are all extremely lengthy.

| Checkpoint | Document | Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Statement of Work | Review | - |

| Preliminary Design Review | Review | Presentation |

| Critical Design Review | Review | Presentation |

| Flight Readiness Review | Review | Presentation |

We also had to dress up

We also had to dress up

Marshall Space Flight Center

We survived the entire project timeline. Not unscathed but still really excited. We drove our MAV and AGSE all the way from Madison, Wisconsin to Huntsville, Alabama so that they wouldn’t get damaged during the shipping process. But of course, the AGSE got damaged anyways.

When we unloaded our AGSE at the Marshall Space Flight Center, we discovered that the engine loader (which shoves an electrical wire into the motor to ignite the fuel with an shock) wasn’t actuating properly. There was a half an our of panic as we ran as many diagnostics as we could, aka looking at and touching everything. We finally found that some of the solder had jiggled loose during the transport. With a huge sigh of relief we soldered everything back together extra securely.

Thankfully nothing else broke.

After a day of presentations, judging began the following day. For the MAV, we flew our rocket to roughly 5100ft, so within the one mile apogee limit and pretty close. For the AGSE, the judging was based on the time it took to complete the entire grabbing, loading, and prepping sequence.

We ended up scoring pretty well and got the second place prize.

We had already re-soldered. Our mentor just wanted an nice photo

We had already re-soldered. Our mentor just wanted an nice photo

Flying High

We were obviously elated to have won the second place prize at the competition. Even more exciting was that we had completed the project at all. For a group of high school students, this was a first of its kind type of experience. I had never worked on something so complex before. I had never worked so closely and intensely with so many other people before. And I had certainly never had to communicated with NASA engineers in such detail before.

If I could save one thing from my high school experience, the Centennial Challenge would definitely be at the top of the priority list.